The Caterpillars are Coming!

by Rob Sproule

We all remember the “the tent caterpillar years”, and most of us still have stories of how, when we were young, they’d sound like rain falling from trees and there would be so many on the road that cars would lose traction. Some years we may not see any, but the years we see a lot, we remember.

While their defoliating ways don’t kill trees directly, they will weaken a tree so that opportunistic and potentially dangerous pests and diseases can move in. Preferring trembling aspen, they usually keep to the forest, but on outbreak years they’ll squiggle their way onto city boulevards and backyard gardens, devouring birch, ash, maple, fruit trees, and cotoneaster.

What are They?

The term “tent” refers to a behavior over a specific species, so there’s sometimes confusion over which “tent” caterpillar we’re dealing with at a given time. Caterpillars who “tent”, retreat into a silk tent during cool spring nights so their body temperature doesn’t drop dangerously low.

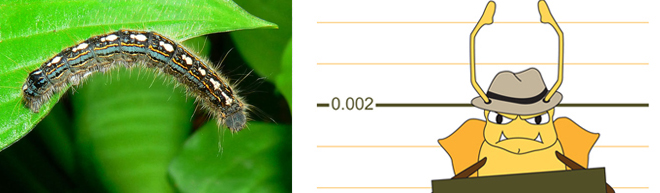

Across the Prairies, the Forest Tent Caterpillar (Malacosoma disstria, to be exact), is the most ravenous. Adults are about 5 cm long with blue stripes on their sides and white, keyhole shaped marks on their back (as if you need to be reminded what they look like).

In our northern climate, outbreaks occur every 6-16 years, depending on conditions, and can last several years. While countless factors can make the outbreak either less or more severe (ex. a hard frost while the egg are hatching will really slow them down), make no mistake about it that the next outbreak is coming.

Controlling Them

During the day, when they’re dispersed and hungry, controlling tent caterpillars can seem impossible to control. A strong jet of water from a garden hose is an amusing way to send them flying, but the best way to really control their numbers is to target their egg sacks.

Female moths lay their eggs in brown, oval-shaped rings on aspen and other favourite trees, where they’re clearly visible from leaf drop in the fall through to their spring hatch. Scrape off whatever egg masses you can reach with a dull blade.

Before you throw the egg masses away, remember that they’re often home to beneficial (stingless) parasitic wasps. Leave the egg mass in a place where it won’t be covered in snow, but where emerging caterpillars don’t have quick access to food. The caterpillars will starve and the wasps will emerge to help control the populations that were too high to reach.

After hatching in the spring, the caterpillars are mostly finished their pillaging by mid-summer, when they retreat into cocoons to emerge as furry brown moths. The cocoons, which we all remember from outbreak years, are grape-sized white silken clumps nestled on house siding, on trees, and pretty much anywhere there’s a small alcove. Destroying these will prevent the moths from emerging and, by extension, will prevent the eggs from being laid for the next season.

The damage is usually only aesthetic, but if you must resort to spraying, there are several environmentally friendly options available.